|

Apprenticeship

Learning in Interdisciplinary and Multi-cultural Environments / the

Tejido Group from Panama to Palestine.

Excerpts from

an Article published by Frederickson in: The International Journal

of Design Education; Vol.6, Issue 3; 2013.

Introduction: for the past thirty-five years the Tejido Group has

developed into an interdisciplinary and collaborative applied

research program in which faculty, students and professionals in

Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Planning and Business

Management collaborate in apprenticeship-style

learning

environments. Tejido is also an international and multi-cultural

experience focused on a wide range of project types

including: sustainable community development, urban and small town

revitalization, urban waterfront design, coastal planning, campus

master planning, and sustainable tourism development projects in the

United States, Latin America and the Middle-East. Tejido has

attempted to remain nimble in its ability to adjust and adapt to

change within the profession, the projects and the student profile.

This in turn, asks that we continually review our process, product,

participant selection and training, and at times even suggests that

we redefine our purpose. Our founding principles initially arose

through affinity with the Bauhausian theory and the early writings

of J. Dewey and later D. Schön, and have now migrated into study

regarding design education and cognitive apprenticeship learning.

The following introduces the purpose, process and products of the

Tejido Group through review of recent projects in Panama and in

Palestine, including discussion of the often innovative and at times

unpredictable educational and professional outcomes.

Project selection: Tejido selects projects in which it wishes to

participate based on several criteria: 1) project uniqueness and

pedagogic value in developing our students into exceptional

practicing professionals; 2) client need; 3) the project’s potential

impact on society and the environment. Although Tejido has and

continues to develop projects through the construction document

phase, we primarily focus on the generation of conceptual

alternatives for our clients. We concentrate our efforts on

developing innovative concepts through the application of research

initiative. learning

environments. Tejido is also an international and multi-cultural

experience focused on a wide range of project types

including: sustainable community development, urban and small town

revitalization, urban waterfront design, coastal planning, campus

master planning, and sustainable tourism development projects in the

United States, Latin America and the Middle-East. Tejido has

attempted to remain nimble in its ability to adjust and adapt to

change within the profession, the projects and the student profile.

This in turn, asks that we continually review our process, product,

participant selection and training, and at times even suggests that

we redefine our purpose. Our founding principles initially arose

through affinity with the Bauhausian theory and the early writings

of J. Dewey and later D. Schön, and have now migrated into study

regarding design education and cognitive apprenticeship learning.

The following introduces the purpose, process and products of the

Tejido Group through review of recent projects in Panama and in

Palestine, including discussion of the often innovative and at times

unpredictable educational and professional outcomes.

Project selection: Tejido selects projects in which it wishes to

participate based on several criteria: 1) project uniqueness and

pedagogic value in developing our students into exceptional

practicing professionals; 2) client need; 3) the project’s potential

impact on society and the environment. Although Tejido has and

continues to develop projects through the construction document

phase, we primarily focus on the generation of conceptual

alternatives for our clients. We concentrate our efforts on

developing innovative concepts through the application of research

initiative.

Unlike associations with traditional design and planning offices,

Tejido offers clients an opportunity to afford in-depth applied

research, and the subsequent generation of alternative concepts

prior to design development and construction documents. In

"real-world" situations, the conceptual design process is often

foreshortened when financial resources are strictly limited. As we

are essentially a non-profit organization dedicated to the education

of our students and the needs of our clients, we can afford to focus

our efforts on pre-design research and schematic exploration with

our clients in developing complex, yet tailored master planning

solutions. We see our relationship with practicing professionals as

one of project creation and not of direct competition. We render

conceptual design and planning services that otherwise could not be

afforded. Tejido assists clients in developing their ideas to the

point where they are ready to seek the services of professionals in

the design development and construction document phases. The master

planning documents we develop become excellent tools for our clients

in the solicitation of international, federal, state and private

funding. Many past clients have been awarded substantial development

grants, and these funds were then used to hire professional firms to

execute the design and planning concepts outlined in our conceptual

master planning documents. We collaborate with host country

counterparts in our international projects in both project selection

and in the programmatic development process. We also work in

interdisciplinary and international teams when abroad as a means of

ensuring project relevance as well as guaranteeing that all

participants, including government agencies and NGO's, are committed

collaborators. This of course, requires that all participants

effectively communicate desired pedagogical and design outcomes for

the studio. General sequencing and scheduling strategies are then

discussed and developed, and alternative project programs and sites

are examined. The host country participants most often take the lead

in these tasks as they best understand what projects are most

relevant to the needs of their communities. They are also better

prepared to articulate central economic, environmental and social

issues surrounding the projects.

Participant selection: the globalization of our curriculum is a

principal directive within Tejido and includes the development of

our students into exceptional practitioners fully capable of working

within a

range of international fora. As we often work in politically and

economically complex multicultural scenarios, selection of

potentially effective participants is essential. The call for

student and faculty volunteers is in itself a useful pre-selection

mechanism. When we ask for volunteers to work in the refugee camps

of Palestine, only a select group of individuals usually steps

forward. Our selection interviews reveal that most often these

individuals are predisposed toward international work and that they

are interested in developing a professional set of skills that

enable them to function in distressed urban areas around the world.

They are usually adventurous at heart, and want to develop a

professional and personal relevancy in their ability to address

global developmental issues. They usually understand that the

globalization of the design and planning professions is requiring of

them a new, flexible and comprehensive repertoire of design and

planning responses to an array of complex urban development issues. Participant selection: the globalization of our curriculum is a

principal directive within Tejido and includes the development of

our students into exceptional practitioners fully capable of working

within a

range of international fora. As we often work in politically and

economically complex multicultural scenarios, selection of

potentially effective participants is essential. The call for

student and faculty volunteers is in itself a useful pre-selection

mechanism. When we ask for volunteers to work in the refugee camps

of Palestine, only a select group of individuals usually steps

forward. Our selection interviews reveal that most often these

individuals are predisposed toward international work and that they

are interested in developing a professional set of skills that

enable them to function in distressed urban areas around the world.

They are usually adventurous at heart, and want to develop a

professional and personal relevancy in their ability to address

global developmental issues. They usually understand that the

globalization of the design and planning professions is requiring of

them a new, flexible and comprehensive repertoire of design and

planning responses to an array of complex urban development issues.

Pre-immersion

Process: we have employed cultural immersion strategies from a

number of international organizations including Peace Corps, UNESCO

and the U.S. Department of State/ USAID. Prior to travel we immerse

potential candidates in a series of orientation seminars that

introduce them to key economic, political, environmental and

cultural issues of the host country. Language and cultural training

along with guest speakers and the viewing of relevant documentaries

are quite effective in introducing participants to the realities of

the task set before them. We also develop in-country immersion

experiences for student volunteers prior

to engaging in design

activities. For instance, the Palestine project allowed our students

several days residence in old city Jerusalem prior to traveling on

to our housing and project site near Ramallah. This visit assisted

our students in familiarizing themselves with the diverse cultural,

political, linguistic and historical aspects of the region, thereby

reducing the inevitable "culture shock" felt by most individuals in

similar situations. The first early morning call to prayer from the Al-Aqsa mosque adjacent to our hostel created quite a revelation in our

students, and the realization that, "we're not in Kansas anymore"

became vividly apparent. The streets, the architecture, the food,

the music, the languages, the odors, the behaviors slowly began to

integrate our daily realities. Our design and planning processes

have been hybridized and developed through study of ideation and

concept generation and development strategies developed within a

number of exceptional design firms. to engaging in design

activities. For instance, the Palestine project allowed our students

several days residence in old city Jerusalem prior to traveling on

to our housing and project site near Ramallah. This visit assisted

our students in familiarizing themselves with the diverse cultural,

political, linguistic and historical aspects of the region, thereby

reducing the inevitable "culture shock" felt by most individuals in

similar situations. The first early morning call to prayer from the Al-Aqsa mosque adjacent to our hostel created quite a revelation in our

students, and the realization that, "we're not in Kansas anymore"

became vividly apparent. The streets, the architecture, the food,

the music, the languages, the odors, the behaviors slowly began to

integrate our daily realities. Our design and planning processes

have been hybridized and developed through study of ideation and

concept generation and development strategies developed within a

number of exceptional design firms.

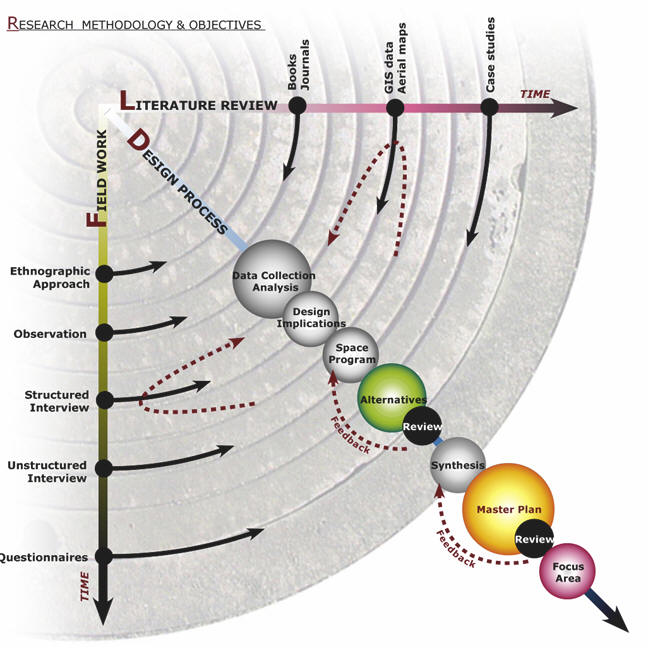

Pre-design Process: although Tejido advance teams visit project

sites prior to project initiation, effective liaison with host

country faculty, students and professionals is also essential during

the pre-design

phases of any project. Months prior to our arrival, host

collaborators assist in project selection as well as preparation of

demographic, cultural, environmental, economic, and site-specific

information for us to digest during pre-immersion activities at

home. We review this data prior to travel and attempt to distill

design and planning precepts/design implications, and sometimes even

fledgling site development concepts that can be tested later on site

and in early charrette sessions with host country participants.

These exercises often help us better understand central issues, site

potentials, and also help us identify what we don't know and what we

need to further investigate. We believe that designers gain insight

and inspiration from a variety of sources. An essential part of our

design and planning process occurs during pre-design research. We

involve our hosts during this phase, and information garnered from a

variety of sources is reviewed and incorporated into the design

intentions of our teams of landscape architects, MBA's, planners,

and architects. Critical socio-cultural, socio-economic,

environmental, functional, and identity-related issues are examined

in depth through hybrid qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

Our designers then distill relevant design and planning implications

from the analysis of the data collected. These bits and pieces of

design ideas (precepts), are eventually incorporated into

comprehensive design and planning concepts as a form of post-factum

hypothesis generation. As part of our pre- central issues, site

potentials, and also help us identify what we don't know and what we

need to further investigate. We believe that designers gain insight

and inspiration from a variety of sources. An essential part of our

design and planning process occurs during pre-design research. We

involve our hosts during this phase, and information garnered from a

variety of sources is reviewed and incorporated into the design

intentions of our teams of landscape architects, MBA's, planners,

and architects. Critical socio-cultural, socio-economic,

environmental, functional, and identity-related issues are examined

in depth through hybrid qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

Our designers then distill relevant design and planning implications

from the analysis of the data collected. These bits and pieces of

design ideas (precepts), are eventually incorporated into

comprehensive design and planning concepts as a form of post-factum

hypothesis generation. As part of our pre- design research, our

teams and hosts collect information regarding clients and site

through extensive case study analysis, video-tape protocol studies,

and structured interviews and questionnaires. We also undertake

exhaustive site inventories, as well as user-group analysis of the

site and surrounding context. During contextual analysis we spend a

great deal of time on and around the site as non-participant and

participant observers. Some methods we employ approximate those of

ethnographers and are qualitative in nature. While others are quite

factual and employ low inference descriptor variables, we begin with

a large scale contextual analysis – looking for key factors

surrounding the site that may influence our design decisions within

the site. This may involve detailed analysis of aerial photographs

and G.I.S. data. We also photograph the entire site and surrounding

urban and natural contexts – looking for existing positive design

features unique to the site as well as problem areas in need of

attention. These

photographic inventories can become quite interesting in areas that

rarely see Americans. design research, our

teams and hosts collect information regarding clients and site

through extensive case study analysis, video-tape protocol studies,

and structured interviews and questionnaires. We also undertake

exhaustive site inventories, as well as user-group analysis of the

site and surrounding context. During contextual analysis we spend a

great deal of time on and around the site as non-participant and

participant observers. Some methods we employ approximate those of

ethnographers and are qualitative in nature. While others are quite

factual and employ low inference descriptor variables, we begin with

a large scale contextual analysis – looking for key factors

surrounding the site that may influence our design decisions within

the site. This may involve detailed analysis of aerial photographs

and G.I.S. data. We also photograph the entire site and surrounding

urban and natural contexts – looking for existing positive design

features unique to the site as well as problem areas in need of

attention. These

photographic inventories can become quite interesting in areas that

rarely see Americans.

In Birzeit, one of our students was

photographing children playing in a vacant dirt lot and was

instantly surrounded by a large group of very curious children. One

bold child said something in Arabic to our student and then grabbed

her camera and ran into an adjacent derelict structure. The student,

being the intrepid traveler that she is, immediately followed the

child right into a living room to find him busily taking photos of

his entire family. She was eventually invited in and shared a very

pleasant afternoon with the family. That afternoon, this student

began to learn the language and diminish the boundaries. On another

occasion during a site inventory visit outside of Ramallah, three of

our students were walking past a fire station. One of the fireman

polishing an ancient fire engine yelled something and then walked

toward our group. Without a common language the

first few minutes were quite awkward yet the encounter resulted in

an In Birzeit, one of our students was

photographing children playing in a vacant dirt lot and was

instantly surrounded by a large group of very curious children. One

bold child said something in Arabic to our student and then grabbed

her camera and ran into an adjacent derelict structure. The student,

being the intrepid traveler that she is, immediately followed the

child right into a living room to find him busily taking photos of

his entire family. She was eventually invited in and shared a very

pleasant afternoon with the family. That afternoon, this student

began to learn the language and diminish the boundaries. On another

occasion during a site inventory visit outside of Ramallah, three of

our students were walking past a fire station. One of the fireman

polishing an ancient fire engine yelled something and then walked

toward our group. Without a common language the

first few minutes were quite awkward yet the encounter resulted in

an

afternoon

well spent singing songs and sharing a meal in the station. In this

instance, the common language was i-tune generated. We try and

develop a very opportunistic environment regarding design and the

generation of design "ideas". Even during data collection and site

analysis activities we encourage idea formation. We are continually

looking for anything that will give us meaningful lines on paper or

monitor. As a summary task of the "pre-design" phase, all

participant data collection teams make detailed presentations of

their findings to all other Tejido and host design team members. In this

manner information is disseminated to all participants and

collective design synthesis can begin. These presentations include

extensive review of all design precepts generated during the

collection and analysis phases. As mentioned, our process encourages

design activity throughout data collection and analysis. One general

guideline we use is that analysis of fact is incomplete without

discussion of the design implications generated by the existence of

said fact. These implications are discussed, developed, and

faithfully recorded for future synthesis activities. Our

international projects most often manifest themselves as intense

three or four week charrettes. In this foreshortened scenario, we

are most interested in formative not summative feedback. We

understand the importance of host and client participation, and that

formative feedback and thorough research designs are essential to

distinctive design products. afternoon

well spent singing songs and sharing a meal in the station. In this

instance, the common language was i-tune generated. We try and

develop a very opportunistic environment regarding design and the

generation of design "ideas". Even during data collection and site

analysis activities we encourage idea formation. We are continually

looking for anything that will give us meaningful lines on paper or

monitor. As a summary task of the "pre-design" phase, all

participant data collection teams make detailed presentations of

their findings to all other Tejido and host design team members. In this

manner information is disseminated to all participants and

collective design synthesis can begin. These presentations include

extensive review of all design precepts generated during the

collection and analysis phases. As mentioned, our process encourages

design activity throughout data collection and analysis. One general

guideline we use is that analysis of fact is incomplete without

discussion of the design implications generated by the existence of

said fact. These implications are discussed, developed, and

faithfully recorded for future synthesis activities. Our

international projects most often manifest themselves as intense

three or four week charrettes. In this foreshortened scenario, we

are most interested in formative not summative feedback. We

understand the importance of host and client participation, and that

formative feedback and thorough research designs are essential to

distinctive design products.

Concept Generation: this phase asks that each individual

participant attempts to synthesize issues uncovered during inventory

and analysis into cohesive planning and design concepts. The

individual concepts are reviewed in exhaustive design synthesis

sessions. Focus is maintained on idea-building activities where

reviewers are charged with the task of making each concept “better”.

Hosts and clients are fully involved during these “formation”

sessions. The relative merits of various design ideas are then

evaluated according to a variety of design and planning ordering

systems that we have embraced over the years. We ask ourselves the

following questions:

-

Is the design economically viable? Does it create jobs and

income sources for the community?

-

Is the design environmentally sensitive? Does it connect or

enhance existing ecosystems? Does it create new habitat? Does it

reduce our carbon footprint?

-

Does the design create opportunities for meaningful social

exchange and learning? Does it embrace the heritage of a site?

-

Does the design circulate effectively? Is it safe? Is it easily

maintained?

-

Has the design identified and created an aesthetic sensibility

appropriate to the history and culture of the region and its

vision of the future?

These

ordering systems are a form of checklist embedded in our design

process, and we believe that an idea’s relevance and usefulness

increases according to the number of different ordering systems that

it engages. For instance, an idea that concerns itself with only

aesthetic issues is not as useful as an idea that fully engages not

only

spatial and image-related issues, but also explores economic,

environmental and social issues as well. A park with flowers is

fine, but a park with flowers that meanders its way through a

community increasing adjacent land values, creating economic infill

incentives within existing infrastructure, mitigating erosion,

promoting urban water harvesting, and encouraging meaningful social

interaction is a richer, more layered and therefore more relevant

concept and eventual urban component. The "best" ideas are recorded,

and in subsequent group and individual charrettes, they are

synthesized into 2 or 3 optimum solutions. At this point, client

review is once again paramount, and alternative concepts are

presented in three dimensional detail, including story boarding and

digital modeling. Once again, we are interested in formative not

summative feedback, and we have found that client feedback is more

lucid and fluent when presented with a series of easily

understandable images and models rather than two dimensional plan

and section drawings. spatial and image-related issues, but also explores economic,

environmental and social issues as well. A park with flowers is

fine, but a park with flowers that meanders its way through a

community increasing adjacent land values, creating economic infill

incentives within existing infrastructure, mitigating erosion,

promoting urban water harvesting, and encouraging meaningful social

interaction is a richer, more layered and therefore more relevant

concept and eventual urban component. The "best" ideas are recorded,

and in subsequent group and individual charrettes, they are

synthesized into 2 or 3 optimum solutions. At this point, client

review is once again paramount, and alternative concepts are

presented in three dimensional detail, including story boarding and

digital modeling. Once again, we are interested in formative not

summative feedback, and we have found that client feedback is more

lucid and fluent when presented with a series of easily

understandable images and models rather than two dimensional plan

and section drawings.

Concept

Development: during this phase, team members are asked to divide

themselves into concept development teams

according to their

personal philosophical alignments regarding the alternative concepts

at hand. Each of the alternatives will then receive additional

attention. Prototypical focus areas located within the planning

concept are identified and developed in greater detail. Ideas from

these focus areas may have application to other areas contained

within the concept. Ideation has been known to stall at times, and

as design inevitably demands recursion, we may jump back into

individual or group charrette activities. At other times, we might

revisit data collection and analysis phases to better inform our

process through the collection of new information or the analysis of

old data through new eyes. Internal / external reviews are

exhaustive and involved during this period. It is critical that

participants have mastered small group dynamics by this stage in the

process. Respect and positive idea building are the tools of choice

during exhaustive and potentially contentious design tasks. according to their

personal philosophical alignments regarding the alternative concepts

at hand. Each of the alternatives will then receive additional

attention. Prototypical focus areas located within the planning

concept are identified and developed in greater detail. Ideas from

these focus areas may have application to other areas contained

within the concept. Ideation has been known to stall at times, and

as design inevitably demands recursion, we may jump back into

individual or group charrette activities. At other times, we might

revisit data collection and analysis phases to better inform our

process through the collection of new information or the analysis of

old data through new eyes. Internal / external reviews are

exhaustive and involved during this period. It is critical that

participants have mastered small group dynamics by this stage in the

process. Respect and positive idea building are the tools of choice

during exhaustive and potentially contentious design tasks.

Working Environment: we have been fortunate to have had the

opportunity to explore and at times, develop new collaborative

environments and methods of design. We have found that above all

else, the process

should remain fun; it seems that we often forget what initially drew

us to the design professions. This usually means equitable

opportunity to participate and share ideas in a respectful and

energetic learning environment. Collaborative design can be a

miserable experience, or it can be delightful. We believe that

enthusiasm for the material, the process, and the people involved in

design enables us to effectively build learning environments where

ideas flow freely, unimpeded by excessively harsh criticism, and

where the advantages of collaboration are consistently apparent. In

this context enthusiasm can become motivational, and could be

described as an enabling process where participants listen,

question, reflect, empathize, and advise

in sincere, non-manipulative manners. The task is to look for

strengths and possibilities rather than core-defects and

inevitabilities. Given the complex nature of the global political,

socio-econo mic and environmental contexts within which we often

work, internal and external cultural and political schisms are at

times all too apparent. Yet conversely, we often find that cultural

and professional commonalities also emerge and become increasingly

apparent to all participants involved. We also find that these

experiences begin to catalyze better understanding of the potential

influences and confines inherent in our design and planning

professions regarding their ability to effect meaningful change in

urban and small town fabrics. We seek to develop learning

environments where mutual interests become increasingly apparent;

where participants begin to realize that they are in the process of

acquiring an array of global professional skills capable of

effecting consequential change; and if we are fortunate enough, an

environment where a shared sentiment begins to emerge that we are a

part of something significant and enduring. mic and environmental contexts within which we often

work, internal and external cultural and political schisms are at

times all too apparent. Yet conversely, we often find that cultural

and professional commonalities also emerge and become increasingly

apparent to all participants involved. We also find that these

experiences begin to catalyze better understanding of the potential

influences and confines inherent in our design and planning

professions regarding their ability to effect meaningful change in

urban and small town fabrics. We seek to develop learning

environments where mutual interests become increasingly apparent;

where participants begin to realize that they are in the process of

acquiring an array of global professional skills capable of

effecting consequential change; and if we are fortunate enough, an

environment where a shared sentiment begins to emerge that we are a

part of something significant and enduring.

Implementation

Strategies: our approach to phasing avoids purely chronological

approaches, and focuses our energy on developing situational matrices

for our clients. This type of phasing is based upon occurrences in the

economy, demographics, political environments, or environmental contexts

of the project, i.e. interest rates, new housing starts, environmental

regulations, etc. We develop discreet development packages for our

clients, and we call these modules of development. Given the appropriate

political and economic environment, any one (or more) of these modules can be

implemented independently from the others.

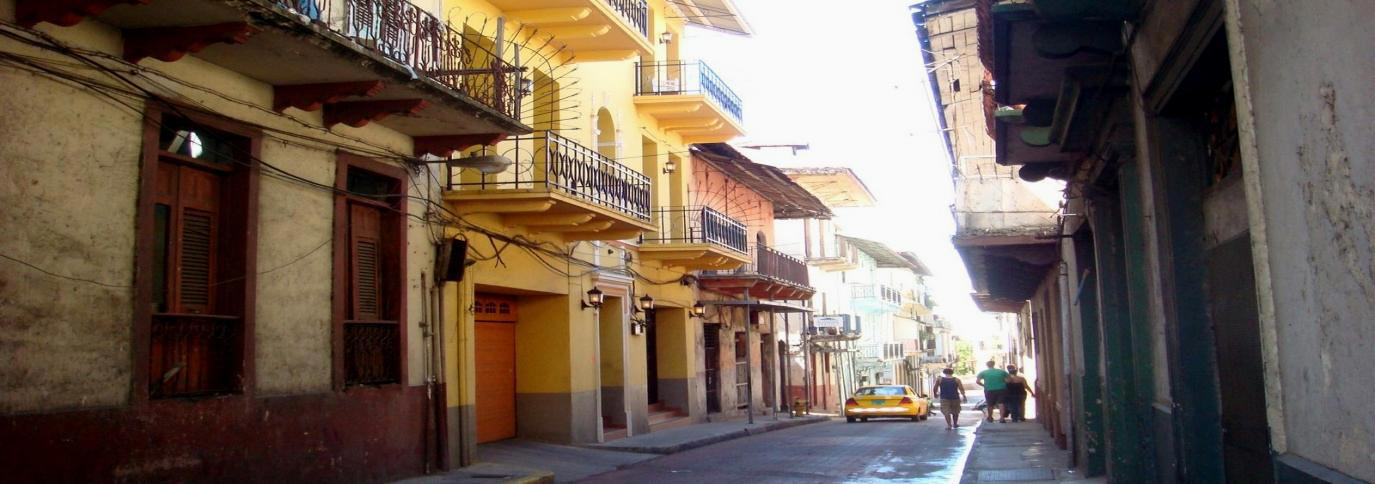

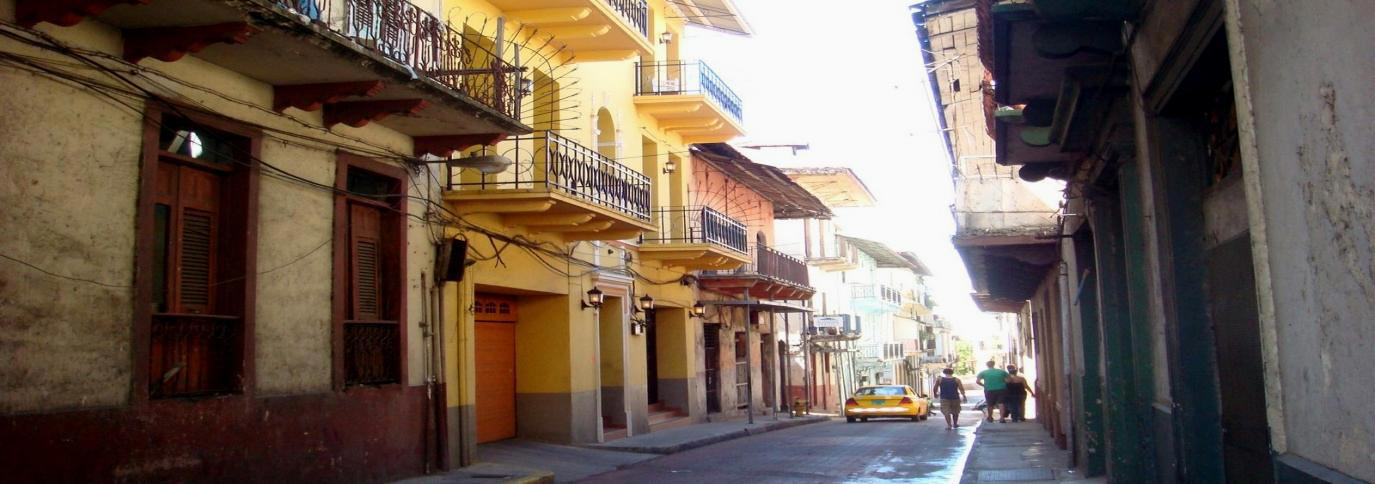

Product: the following is a brief discussion of products

resulting from our processes. We will also attempt to point out and

discuss defining moments in

the development of our design ideas as

well as in the maturation of our students into global practitioners

and citizens of the world. In both Palestine and in Panama we

were

pleased with the relevance and usefulness of both our design and

pedagogic products. Several of our students are now living and

working in both locations following these projects. This spring

semester, Panamanian faculty and students are visiting our

University to participate with us on local projects in Arizona. This

reciprocation is difficult for the Palestinian students as visa

issues have prevented their travel to date, but we will certainly

keep trying to make this work. In Panama our client was the Governor

of Panama, Mayin Correa, and she received our revitalization master

plan with enthusiasm. The design has gone through a preliminary cost

estimating process and will be presented to the President of Panama

- Ricardo Martinelli for approval this coming December. The

Palestine project was very well received by the Mayor of Birzeit -

Yusef Nasser, RIWAQ and UNRWA. As funding is a critical issue for

the Palestinians, we created a "modules of development" phasing

strategy for them that allows the project to be employed through a

number of discrete developmental packages that can be initiated

individually given the appropriate political and economic

environment. were

pleased with the relevance and usefulness of both our design and

pedagogic products. Several of our students are now living and

working in both locations following these projects. This spring

semester, Panamanian faculty and students are visiting our

University to participate with us on local projects in Arizona. This

reciprocation is difficult for the Palestinian students as visa

issues have prevented their travel to date, but we will certainly

keep trying to make this work. In Panama our client was the Governor

of Panama, Mayin Correa, and she received our revitalization master

plan with enthusiasm. The design has gone through a preliminary cost

estimating process and will be presented to the President of Panama

- Ricardo Martinelli for approval this coming December. The

Palestine project was very well received by the Mayor of Birzeit -

Yusef Nasser, RIWAQ and UNRWA. As funding is a critical issue for

the Palestinians, we created a "modules of development" phasing

strategy for them that allows the project to be employed through a

number of discrete developmental packages that can be initiated

individually given the appropriate political and economic

environment.

Team Birzeit

Team Panama |

learning

environments. Tejido is also an international and multi-cultural

experience focused on a wide range of project types

including: sustainable community development, urban and small town

revitalization, urban waterfront design, coastal planning, campus

master planning, and sustainable tourism development projects in the

United States, Latin America and the Middle-East. Tejido has

attempted to remain nimble in its ability to adjust and adapt to

change within the profession, the projects and the student profile.

This in turn, asks that we continually review our process, product,

participant selection and training, and at times even suggests that

we redefine our purpose. Our founding principles initially arose

through affinity with the Bauhausian theory and the early writings

of J. Dewey and later D. Schön, and have now migrated into study

regarding design education and cognitive apprenticeship learning.

The following introduces the purpose, process and products of the

Tejido Group through review of recent projects in Panama and in

Palestine, including discussion of the often innovative and at times

unpredictable educational and professional outcomes.

Project selection: Tejido selects projects in which it wishes to

participate based on several criteria: 1) project uniqueness and

pedagogic value in developing our students into exceptional

practicing professionals; 2) client need; 3) the project’s potential

impact on society and the environment. Although Tejido has and

continues to develop projects through the construction document

phase, we primarily focus on the generation of conceptual

alternatives for our clients. We concentrate our efforts on

developing innovative concepts through the application of research

initiative.

learning

environments. Tejido is also an international and multi-cultural

experience focused on a wide range of project types

including: sustainable community development, urban and small town

revitalization, urban waterfront design, coastal planning, campus

master planning, and sustainable tourism development projects in the

United States, Latin America and the Middle-East. Tejido has

attempted to remain nimble in its ability to adjust and adapt to

change within the profession, the projects and the student profile.

This in turn, asks that we continually review our process, product,

participant selection and training, and at times even suggests that

we redefine our purpose. Our founding principles initially arose

through affinity with the Bauhausian theory and the early writings

of J. Dewey and later D. Schön, and have now migrated into study

regarding design education and cognitive apprenticeship learning.

The following introduces the purpose, process and products of the

Tejido Group through review of recent projects in Panama and in

Palestine, including discussion of the often innovative and at times

unpredictable educational and professional outcomes.

Project selection: Tejido selects projects in which it wishes to

participate based on several criteria: 1) project uniqueness and

pedagogic value in developing our students into exceptional

practicing professionals; 2) client need; 3) the project’s potential

impact on society and the environment. Although Tejido has and

continues to develop projects through the construction document

phase, we primarily focus on the generation of conceptual

alternatives for our clients. We concentrate our efforts on

developing innovative concepts through the application of research

initiative.

Participant selection: the globalization of our curriculum is a

principal directive within Tejido and includes the development of

our students into exceptional practitioners fully capable of working

within a

range of international fora. As we often work in politically and

economically complex multicultural scenarios, selection of

potentially effective participants is essential. The call for

student and faculty volunteers is in itself a useful pre-selection

mechanism. When we ask for volunteers to work in the refugee camps

of Palestine, only a select group of individuals usually steps

forward. Our selection interviews reveal that most often these

individuals are predisposed toward international work and that they

are interested in developing a professional set of skills that

enable them to function in distressed urban areas around the world.

They are usually adventurous at heart, and want to develop a

professional and personal relevancy in their ability to address

global developmental issues. They usually understand that the

globalization of the design and planning professions is requiring of

them a new, flexible and comprehensive repertoire of design and

planning responses to an array of complex urban development issues.

Participant selection: the globalization of our curriculum is a

principal directive within Tejido and includes the development of

our students into exceptional practitioners fully capable of working

within a

range of international fora. As we often work in politically and

economically complex multicultural scenarios, selection of

potentially effective participants is essential. The call for

student and faculty volunteers is in itself a useful pre-selection

mechanism. When we ask for volunteers to work in the refugee camps

of Palestine, only a select group of individuals usually steps

forward. Our selection interviews reveal that most often these

individuals are predisposed toward international work and that they

are interested in developing a professional set of skills that

enable them to function in distressed urban areas around the world.

They are usually adventurous at heart, and want to develop a

professional and personal relevancy in their ability to address

global developmental issues. They usually understand that the

globalization of the design and planning professions is requiring of

them a new, flexible and comprehensive repertoire of design and

planning responses to an array of complex urban development issues.

to engaging in design

activities. For instance, the Palestine project allowed our students

several days residence in old city Jerusalem prior to traveling on

to our housing and project site near Ramallah. This visit assisted

our students in familiarizing themselves with the diverse cultural,

political, linguistic and historical aspects of the region, thereby

reducing the inevitable "culture shock" felt by most individuals in

similar situations. The first early morning call to prayer from the Al-Aqsa mosque adjacent to our hostel created quite a revelation in our

students, and the realization that, "we're not in Kansas anymore"

became vividly apparent. The streets, the architecture, the food,

the music, the languages, the odors, the behaviors slowly began to

integrate our daily realities. Our design and planning processes

have been hybridized and developed through study of ideation and

concept generation and development strategies developed within a

number of exceptional design firms.

to engaging in design

activities. For instance, the Palestine project allowed our students

several days residence in old city Jerusalem prior to traveling on

to our housing and project site near Ramallah. This visit assisted

our students in familiarizing themselves with the diverse cultural,

political, linguistic and historical aspects of the region, thereby

reducing the inevitable "culture shock" felt by most individuals in

similar situations. The first early morning call to prayer from the Al-Aqsa mosque adjacent to our hostel created quite a revelation in our

students, and the realization that, "we're not in Kansas anymore"

became vividly apparent. The streets, the architecture, the food,

the music, the languages, the odors, the behaviors slowly began to

integrate our daily realities. Our design and planning processes

have been hybridized and developed through study of ideation and

concept generation and development strategies developed within a

number of exceptional design firms.  central issues, site

potentials, and also help us identify what we don't know and what we

need to further investigate. We believe that designers gain insight

and inspiration from a variety of sources. An essential part of our

design and planning process occurs during pre-design research. We

involve our hosts during this phase, and information garnered from a

variety of sources is reviewed and incorporated into the design

intentions of our teams of landscape architects, MBA's, planners,

and architects. Critical socio-cultural, socio-economic,

environmental, functional, and identity-related issues are examined

in depth through hybrid qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

Our designers then distill relevant design and planning implications

from the analysis of the data collected. These bits and pieces of

design ideas (precepts), are eventually incorporated into

comprehensive design and planning concepts as a form of post-factum

hypothesis generation. As part of our pre-

central issues, site

potentials, and also help us identify what we don't know and what we

need to further investigate. We believe that designers gain insight

and inspiration from a variety of sources. An essential part of our

design and planning process occurs during pre-design research. We

involve our hosts during this phase, and information garnered from a

variety of sources is reviewed and incorporated into the design

intentions of our teams of landscape architects, MBA's, planners,

and architects. Critical socio-cultural, socio-economic,

environmental, functional, and identity-related issues are examined

in depth through hybrid qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

Our designers then distill relevant design and planning implications

from the analysis of the data collected. These bits and pieces of

design ideas (precepts), are eventually incorporated into

comprehensive design and planning concepts as a form of post-factum

hypothesis generation. As part of our pre- design research, our

teams and hosts collect information regarding clients and site

through extensive case study analysis, video-tape protocol studies,

and structured interviews and questionnaires. We also undertake

exhaustive site inventories, as well as user-group analysis of the

site and surrounding context. During contextual analysis we spend a

great deal of time on and around the site as non-participant and

participant observers. Some methods we employ approximate those of

ethnographers and are qualitative in nature. While others are quite

factual and employ low inference descriptor variables, we begin with

a large scale contextual analysis – looking for key factors

surrounding the site that may influence our design decisions within

the site. This may involve detailed analysis of aerial photographs

and G.I.S. data. We also photograph the entire site and surrounding

urban and natural contexts – looking for existing positive design

features unique to the site as well as problem areas in need of

attention. These

photographic inventories can become quite interesting in areas that

rarely see Americans.

design research, our

teams and hosts collect information regarding clients and site

through extensive case study analysis, video-tape protocol studies,

and structured interviews and questionnaires. We also undertake

exhaustive site inventories, as well as user-group analysis of the

site and surrounding context. During contextual analysis we spend a

great deal of time on and around the site as non-participant and

participant observers. Some methods we employ approximate those of

ethnographers and are qualitative in nature. While others are quite

factual and employ low inference descriptor variables, we begin with

a large scale contextual analysis – looking for key factors

surrounding the site that may influence our design decisions within

the site. This may involve detailed analysis of aerial photographs

and G.I.S. data. We also photograph the entire site and surrounding

urban and natural contexts – looking for existing positive design

features unique to the site as well as problem areas in need of

attention. These

photographic inventories can become quite interesting in areas that

rarely see Americans.

In Birzeit, one of our students was

photographing children playing in a vacant dirt lot and was

instantly surrounded by a large group of very curious children. One

bold child said something in Arabic to our student and then grabbed

her camera and ran into an adjacent derelict structure. The student,

being the intrepid traveler that she is, immediately followed the

child right into a living room to find him busily taking photos of

his entire family. She was eventually invited in and shared a very

pleasant afternoon with the family. That afternoon, this student

began to learn the language and diminish the boundaries. On another

occasion during a site inventory visit outside of Ramallah, three of

our students were walking past a fire station. One of the fireman

polishing an ancient fire engine yelled something and then walked

toward our group. Without a common language the

first few minutes were quite awkward yet the encounter resulted in

an

In Birzeit, one of our students was

photographing children playing in a vacant dirt lot and was

instantly surrounded by a large group of very curious children. One

bold child said something in Arabic to our student and then grabbed

her camera and ran into an adjacent derelict structure. The student,

being the intrepid traveler that she is, immediately followed the

child right into a living room to find him busily taking photos of

his entire family. She was eventually invited in and shared a very

pleasant afternoon with the family. That afternoon, this student

began to learn the language and diminish the boundaries. On another

occasion during a site inventory visit outside of Ramallah, three of

our students were walking past a fire station. One of the fireman

polishing an ancient fire engine yelled something and then walked

toward our group. Without a common language the

first few minutes were quite awkward yet the encounter resulted in

an

afternoon

well spent singing songs and sharing a meal in the station. In this

instance, the common language was i-tune generated. We try and

develop a very opportunistic environment regarding design and the

generation of design "ideas". Even during data collection and site

analysis activities we encourage idea formation. We are continually

looking for anything that will give us meaningful lines on paper or

monitor. As a summary task of the "pre-design" phase, all

participant data collection teams make detailed presentations of

their findings to all other Tejido and host design team members. In this

manner information is disseminated to all participants and

collective design synthesis can begin. These presentations include

extensive review of all design precepts generated during the

collection and analysis phases. As mentioned, our process encourages

design activity throughout data collection and analysis. One general

guideline we use is that analysis of fact is incomplete without

discussion of the design implications generated by the existence of

said fact. These implications are discussed, developed, and

faithfully recorded for future synthesis activities. Our

international projects most often manifest themselves as intense

three or four week charrettes. In this foreshortened scenario, we

are most interested in formative not summative feedback. We

understand the importance of host and client participation, and that

formative feedback and thorough research designs are essential to

distinctive design products.

afternoon

well spent singing songs and sharing a meal in the station. In this

instance, the common language was i-tune generated. We try and

develop a very opportunistic environment regarding design and the

generation of design "ideas". Even during data collection and site

analysis activities we encourage idea formation. We are continually

looking for anything that will give us meaningful lines on paper or

monitor. As a summary task of the "pre-design" phase, all

participant data collection teams make detailed presentations of

their findings to all other Tejido and host design team members. In this

manner information is disseminated to all participants and

collective design synthesis can begin. These presentations include

extensive review of all design precepts generated during the

collection and analysis phases. As mentioned, our process encourages

design activity throughout data collection and analysis. One general

guideline we use is that analysis of fact is incomplete without

discussion of the design implications generated by the existence of

said fact. These implications are discussed, developed, and

faithfully recorded for future synthesis activities. Our

international projects most often manifest themselves as intense

three or four week charrettes. In this foreshortened scenario, we

are most interested in formative not summative feedback. We

understand the importance of host and client participation, and that

formative feedback and thorough research designs are essential to

distinctive design products. spatial and image-related issues, but also explores economic,

environmental and social issues as well. A park with flowers is

fine, but a park with flowers that meanders its way through a

community increasing adjacent land values, creating economic infill

incentives within existing infrastructure, mitigating erosion,

promoting urban water harvesting, and encouraging meaningful social

interaction is a richer, more layered and therefore more relevant

concept and eventual urban component. The "best" ideas are recorded,

and in subsequent group and individual charrettes, they are

synthesized into 2 or 3 optimum solutions. At this point, client

review is once again paramount, and alternative concepts are

presented in three dimensional detail, including story boarding and

digital modeling. Once again, we are interested in formative not

summative feedback, and we have found that client feedback is more

lucid and fluent when presented with a series of easily

understandable images and models rather than two dimensional plan

and section drawings.

spatial and image-related issues, but also explores economic,

environmental and social issues as well. A park with flowers is

fine, but a park with flowers that meanders its way through a

community increasing adjacent land values, creating economic infill

incentives within existing infrastructure, mitigating erosion,

promoting urban water harvesting, and encouraging meaningful social

interaction is a richer, more layered and therefore more relevant

concept and eventual urban component. The "best" ideas are recorded,

and in subsequent group and individual charrettes, they are

synthesized into 2 or 3 optimum solutions. At this point, client

review is once again paramount, and alternative concepts are

presented in three dimensional detail, including story boarding and

digital modeling. Once again, we are interested in formative not

summative feedback, and we have found that client feedback is more

lucid and fluent when presented with a series of easily

understandable images and models rather than two dimensional plan

and section drawings.  according to their

personal philosophical alignments regarding the alternative concepts

at hand. Each of the alternatives will then receive additional

attention. Prototypical focus areas located within the planning

concept are identified and developed in greater detail. Ideas from

these focus areas may have application to other areas contained

within the concept. Ideation has been known to stall at times, and

as design inevitably demands recursion, we may jump back into

individual or group charrette activities. At other times, we might

revisit data collection and analysis phases to better inform our

process through the collection of new information or the analysis of

old data through new eyes. Internal / external reviews are

exhaustive and involved during this period. It is critical that

participants have mastered small group dynamics by this stage in the

process. Respect and positive idea building are the tools of choice

during exhaustive and potentially contentious design tasks.

according to their

personal philosophical alignments regarding the alternative concepts

at hand. Each of the alternatives will then receive additional

attention. Prototypical focus areas located within the planning

concept are identified and developed in greater detail. Ideas from

these focus areas may have application to other areas contained

within the concept. Ideation has been known to stall at times, and

as design inevitably demands recursion, we may jump back into

individual or group charrette activities. At other times, we might

revisit data collection and analysis phases to better inform our

process through the collection of new information or the analysis of

old data through new eyes. Internal / external reviews are

exhaustive and involved during this period. It is critical that

participants have mastered small group dynamics by this stage in the

process. Respect and positive idea building are the tools of choice

during exhaustive and potentially contentious design tasks. mic and environmental contexts within which we often

work, internal and external cultural and political schisms are at

times all too apparent. Yet conversely, we often find that cultural

and professional commonalities also emerge and become increasingly

apparent to all participants involved. We also find that these

experiences begin to catalyze better understanding of the potential

influences and confines inherent in our design and planning

professions regarding their ability to effect meaningful change in

urban and small town fabrics. We seek to develop learning

environments where mutual interests become increasingly apparent;

where participants begin to realize that they are in the process of

acquiring an array of global professional skills capable of

effecting consequential change; and if we are fortunate enough, an

environment where a shared sentiment begins to emerge that we are a

part of something significant and enduring.

mic and environmental contexts within which we often

work, internal and external cultural and political schisms are at

times all too apparent. Yet conversely, we often find that cultural

and professional commonalities also emerge and become increasingly

apparent to all participants involved. We also find that these

experiences begin to catalyze better understanding of the potential

influences and confines inherent in our design and planning

professions regarding their ability to effect meaningful change in

urban and small town fabrics. We seek to develop learning

environments where mutual interests become increasingly apparent;

where participants begin to realize that they are in the process of

acquiring an array of global professional skills capable of

effecting consequential change; and if we are fortunate enough, an

environment where a shared sentiment begins to emerge that we are a

part of something significant and enduring.  were

pleased with the relevance and usefulness of both our design and

pedagogic products. Several of our students are now living and

working in both locations following these projects. This spring

semester, Panamanian faculty and students are visiting our

University to participate with us on local projects in Arizona. This

reciprocation is difficult for the Palestinian students as visa

issues have prevented their travel to date, but we will certainly

keep trying to make this work. In Panama our client was the Governor

of Panama, Mayin Correa, and she received our revitalization master

plan with enthusiasm. The design has gone through a preliminary cost

estimating process and will be presented to the President of Panama

- Ricardo Martinelli for approval this coming December. The

Palestine project was very well received by the Mayor of Birzeit -

Yusef Nasser, RIWAQ and UNRWA. As funding is a critical issue for

the Palestinians, we created a "modules of development" phasing

strategy for them that allows the project to be employed through a

number of discrete developmental packages that can be initiated

individually given the appropriate political and economic

environment.

were

pleased with the relevance and usefulness of both our design and

pedagogic products. Several of our students are now living and

working in both locations following these projects. This spring

semester, Panamanian faculty and students are visiting our

University to participate with us on local projects in Arizona. This

reciprocation is difficult for the Palestinian students as visa

issues have prevented their travel to date, but we will certainly

keep trying to make this work. In Panama our client was the Governor

of Panama, Mayin Correa, and she received our revitalization master

plan with enthusiasm. The design has gone through a preliminary cost

estimating process and will be presented to the President of Panama

- Ricardo Martinelli for approval this coming December. The

Palestine project was very well received by the Mayor of Birzeit -

Yusef Nasser, RIWAQ and UNRWA. As funding is a critical issue for

the Palestinians, we created a "modules of development" phasing

strategy for them that allows the project to be employed through a

number of discrete developmental packages that can be initiated

individually given the appropriate political and economic

environment.